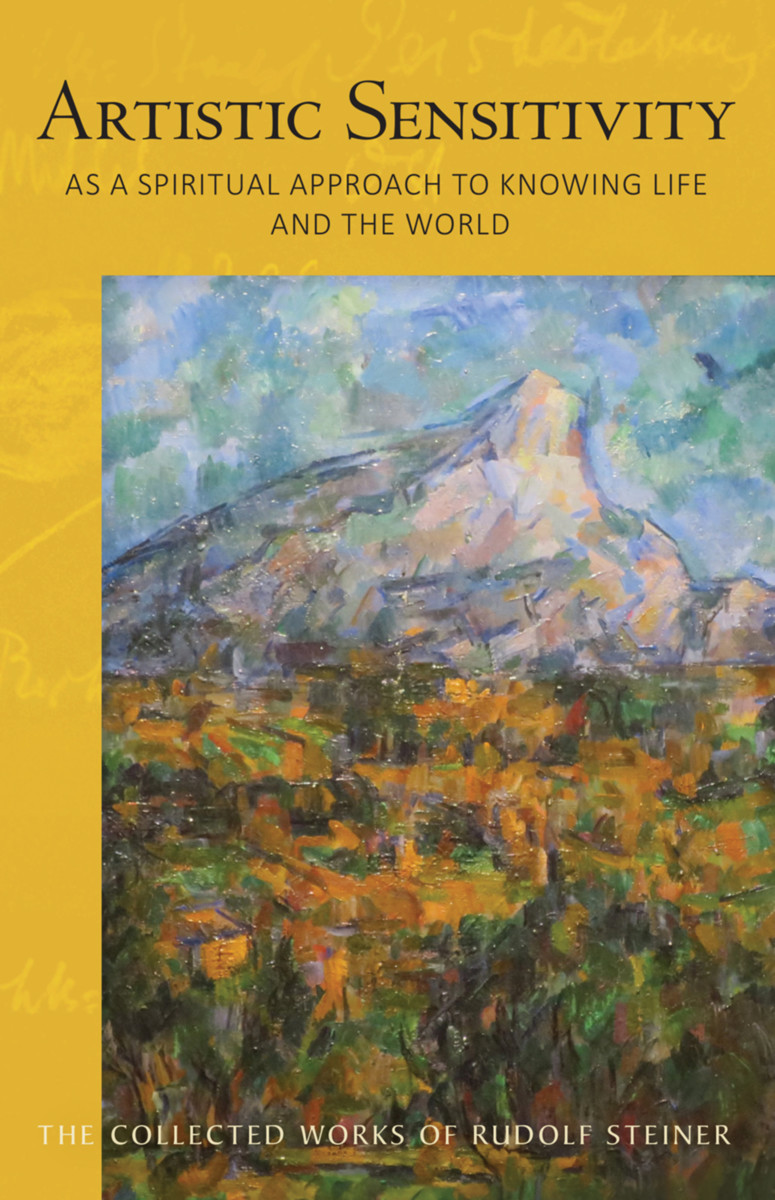

Artistic Sensitivity as a Spiritual Approach to Knowing Life and the World

(CW 161)

- Publisher

SteinerBooks - Published

17th April 2018 - ISBN 9781621481775

- Language English

- Pages 332 pp.

- Size 6" x 9.25"

13 lectures, Dornach, Switzerland, January 9 – May 2, 1915 (CW 161)

“Simply learning the theory of spiritual science is not enough; what matters is having an inner experience of what we learn, and filling our souls with the impulses of spiritual science.... We must also attempt to really bring spiritual science to life, to really let it flow into what we undertake and intend to do. We need to become conscious of the fact that the spiritual-scientific worldview provides something that is meant to engender a new kind of human being in place of the old human being who has come down to us like an heirloom from an earlier stage of Earth evolution. As we do so, we begin to develop the preconditions in ourselves though spiritual science that will help give birth to what is to be born in the future on Earth.” — Rudolf Steiner (lecture 1)

Today’s orthodox notions of science—which is to say, of knowing—are exceedingly narrow; they posit, implicitly or otherwise, that the only knowledge possible, if any, is that of the physical world. But the skeleton key to unlocking the door, behind which lies the root of the problems and difficulties of our age, and thus their solution, is to be able to fully answer this question: What is it to know something? This question lies at the foundation of spiritual science. Rudolf Steiner had first to solve it for himself, pointing the way for others to do the same (in, for example, his Philosophy of Freedom), long before he could give such lectures as these.

Rudolf Steiner’s work and words, still largely undiscovered as compared to their value for humanity, continue to point the way toward a different path—a way of knowing that encompasses the fullness, the breadth and depth of life and the worlds we inhabit. This knowing—which is to say, science—does not ignore or even contradict the narrower physical sciences of technologists and other specialists, but offers an expansive understanding of reality that also includes a deeper engagement with those aspects of our experience that we are told are beyond the ken of science. But is truth not accessible through art? Are poetry and literature, indeed the beauty and wisdom of each human language, not portals through which we can glimpse truths, every bit as real (though of a different order) than those we might grasp through a microscope?

These thirteen lectures were given in Dornach, Switzerland, from January to May 1915, between the fifth and ninth months of World War I. Given the interrupted, fragmented nature of this sequence, one might assume that the lectures could not possibly present a tight, coherent whole. This is not the case. Rudolf Steiner lays down the framework for the series in a concise but detailed manner in the first two lectures, and then goes on to demonstrate in lecture after lecture how, on this basis, many aspects of life reveal the hidden presence and activities of the realities—and the approach—he has established in the framework. In fact, it is humbling to witness Rudolf Steiner’s powers of attention and presence of mind: to see how, after a significant interval, in the same tone of voice and with seamless continuity, he can pick up and further develop and interweave his announced intention: namely, to provide “a detailed look at things we have been considering for years.”

“We experience the lives of many beings, right up to those of the upper hierarchies. If we want to experience an angel, an archangel, or the spirit of an individual, then we must stretch out our thoughts.... The being must be encased in our thoughts. We send our thoughts out and the being slips into them and moves within them. When we perceive a being on Venus or Saturn, it happens because we have allowed our thoughts to extend, and the being from Saturn or Venus has slipped into them.” — Rudolf Steiner (lecture 8)

Artistic Sensitivity as a Spiritual Approach to Knowing Life and the World is a translation from German of Wege der geistigen Erkenntnis und der Erneureung künstlerischer Weltanschauung (GA 161).

C O N T E N T S:

Introduction by Christopher Bamford

Lecture One: Dornach, January 9, 1915

The fourfold nature of the “I” as something outwardly perceptible; as speech and song; as creative fantasy; as inner experience. The richness of diagrams derived from spiritual-scientific work. The significance of Anthroposophy for the renewal of certain aspects of life, such as recitation and song.

Lecture Two: Dornach, January 10, 1915

The continued effects of the old Saturn forces in the formation of human destiny, and of the old Moon forces in the development of the embryo. The changes in the human relationship to thought. The effects of the Sun nature in the philosophical development of humanity. Christian Morgenstern’s sensibility for such things.

Lecture Three: Dornach, January 30, 1915

Genuine art is rooted in the secrets of initiation. The initiation of Brunetto Latini. His influence on Dante and the conception of The Divine Comedy. The effect of the Christ impulse on the unconscious soul forces. Emperor Constantine. The Maid of Orleans. The renewal of the artistic impulse through the knowledge of spiritual science.

Lecture Four: Dornach, February 2, 1915

The maya nature of life on earth. The reflection of various cosmic, pre-birth experiences in the periods of life through the end of childhood. The connection of these experiences with the prior planetary conditions of the earth. The significance of such knowledge for pedagogy. The life of the adult as the reflection of events beyond the visible world. The nature of human freedom. The significance of the moment of death.

Lecture Five: Dornach, February 5, 1915

The difficulty of true self-knowledge. The example of Ernst Mach. Soul forces at work in the subconscious and its concealment in our maya of imagination. The significance of such connections for poetry. The novella The Singer by Herman Grimm, and its accurate description of a secretly significant relationship of destinies.

Lecture Six: Dornach, February 6, 1915

The law of the conservation of energy, introduced by Julius Robert Mayer, is also true in the soul–spiritual realm. The continued effect of the unused etheric forces of people who die early. The spectrum of death and the unlived-out karma contained therein, as shown in the examples of the previously mentioned novella by Herman Grimm and in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. A further example of the same in Herman Grimm’s novel Insurmountable Powers. The separation that begins after death of the human forces that turn toward the cosmos and those that remain connected with the individual. The continued life after death of a soul completely connected with spiritual science: Frau Grosheintz.

Lecture Seven: Dornach, February 7, 1915

Selflessness as a condition for the research into life after death. A verse from Goethe for use in mediating. The awakening of the soul after death as a dampening of an overly strong consciousness. On the unity of the ocean of thought with the multiplicity of individual hierarchical beings. The relationship of artistic activity with post-death experiences. The ripening of art through spiritual-scientific thought. Two examples of modern artists’ fear of the spiritual world. Our connection with the souls of people who die young. Theo Faiss. Frau Colazza. Fritz Mitsche as a model of selflessness and objectivity.

Lecture Eight: Dornach, April 27, 1915

The gaining of suprasensory knowledge through the liberation of spiritual forces from the physical organism. Three forms of clairvoyance and the differences among them. The clairvoyance of the head as the one most appropriate to our time. The penetration of spiritual beings into our thoughts as a demand of the present. The presentiment of this need in the materialist Ludwig Feuerbach. The tendency toward superficiality and inconsequential thinking as an enemy of spiritual science.

Lecture Nine: Dornach, April 28, 1915

Wilhelm Jordan as the renewer of the Nibelungenlied. On the content of the old Nibelungelied. The important personalities of Siegfried and Brunhilde affected by the influence of earlier incarnations. Certain sections from Jordan’s new iteration. The expiration of the old forces of Sun sight, described in the myth of Baldur and Nanna, further explored in the tragedy of the Nibelungelied. Jordan’s presentiment of these connections. A lack of understanding for this in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A letter from Frederick II to Christoph Heinrich Müller as an expression of this lack of understanding. The waning of an inner relationship to speech and Jordan’s attempt at renewing it.

Lecture Ten: Dornach, April 2, 1915

The silencing of the bells from Good Friday through Easter. The ancient Celtic–Germanic connection with the spiritual essence in nature. The mourning of the loss of the feeling for nature expressed in the myth of Baldur’s death. His descent to Hel as an image for the sinking of the living forces of artistic imaging into the unconscious depths of the human soul. The revival of these forces through the resurrected Christ. The mourning of the loss of spiritual nature echoed in the Evangelienharmonie by Otfried von Weissburg. The feeling for the connection of Christ with the forces of nature in the Heliand.

Lecture Eleven: Dornach, April 3, 1915

The mood of the days around Easter. The passage of the Christ through death and burial. His fight against Lucifer and Ahriman. The significance of these events for our coming life on Jupiter. The revival of Earth consciousness within the Jupiter existence. The rescue of the human soul from the power of Lucifer and Ahriman. The Last Judgment by Michelangelo as an expression of an earlier understanding of the Christ. Some words about that by Herman Grimm. Christian Morgenstern’s new understanding of the Christ.

Lecture Twelve: Dornach, May 1, 1915

Some words from the philosopher Otto Liebmann. His hesitation before the gate of Anthroposophy. How thought activity is moved from the etheric body into the astral body through initiation. The etheric body as an instrument of reflection. The formation of an etheric heart. The system of ganglia and its significance for the future. Head clairvoyance through the high development of thought forces. Stomach clairvoyance through reflecting back unconscious drives.

Lecture Thirteen: Dornach, May 2, 1915

The forces of thought and will in their expression following death and during initiation. Becoming conscious of thought events through reflection on what was previously thought. The transformation of our earthly life into an organ of perception for the spiritual world. Exercises for the furthering of our will forces beyond what is normally experienced. Schopenhauer at the gate of spiritual knowledge. The externalization of soul research in experimental psychology. A book by Edwin Starbuck. The necessity of taking up the Christ impulse. An example of a falsification of history.

Editorial and Reference Notes

Rudolf Steiner’s Collected Works

Significant Events in the Life of Rudolf Steiner

Name Index

Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Steiner (b. Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner, 1861–1925) was born in the small village of Kraljevec, Austro-Hungarian Empire (now in Croatia), where he grew up. As a young man, he lived in Weimar and Berlin, where he became a well-published scientific, literary, and philosophical scholar, known especially for his work with Goethe’s scientific writings. Steiner termed his spiritual philosophy anthroposophy, meaning “wisdom of the human being.” As an exceptionally developed seer, he based his work on direct knowledge and perception of spiritual dimensions. He initiated a modern, universal “spiritual science” that is accessible to anyone willing to exercise clear and unbiased thinking. From his spiritual investigations, Steiner provided suggestions for the renewal of numerous activities, including education (general and for special needs), agriculture, medicine, economics, architecture, science, philosophy, Christianity, and the arts. There are currently thousands of schools, clinics, farms, and initiatives in other fields that involve practical work based on the principles Steiner developed. His many published works feature his research into the spiritual nature of human beings, the evolution of the world and humanity, and methods for personal development. He wrote some thirty books and delivered more than six thousand lectures throughout much of Europe. In 1924, Steiner founded the General Anthroposophical Society, which today has branches around the world.